Bill Graham Presents: The Death of Charles Sullivan

The unsolved murder of San Francisco's premiere concert promoter

In a San Francisco Chronicle review of a Stevie Nicks concert in the 1980s, she reminisced about the night her first band, Fritz, opened for Janis Joplin at the world-famous Fillmore Auditorium.

“This guy [was] heckling me, ‘Hey baby, what are you doing?’ And guess who walks onstage? Mr. Bill Graham,” Nicks recounted, referring to the legendary San Francisco concert promoter. “He stomps out on the stage, and I’m not sure who he is, but I know he’s someone. He said [to the heckler], ‘I want you to get out of my fucking Fillmore and never fucking come back to this building ever! And if I ever see you come back, I’ll kill you!’”

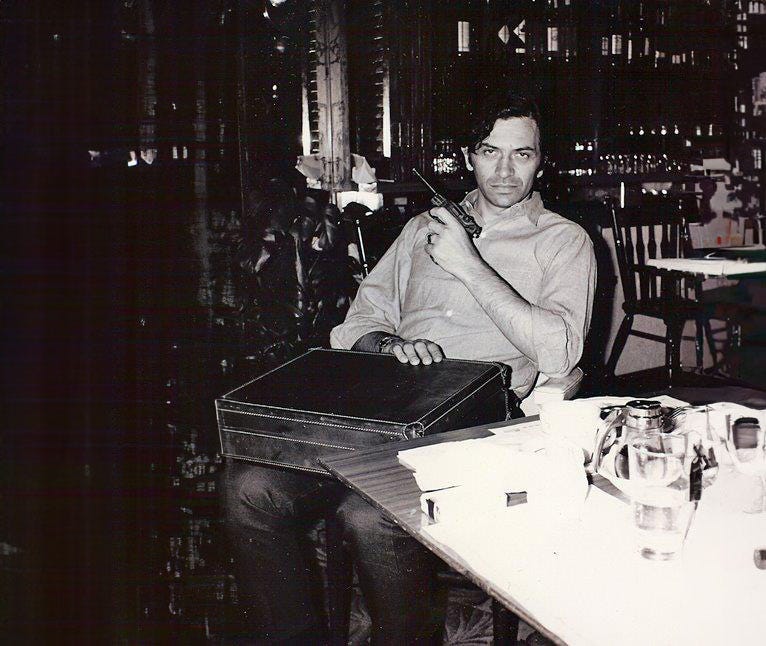

That threat must have sent a chill through the crowd of hippies in attendance at the Fillmore. It was widely believed that Bill Graham had orchestrated the 1966 murder of Charles Sullivan, the "Mayor of Fillmore," a rich and influential black entrepreneur and concert promoter. The motive? To seize control of the famous venue and become the biggest music promoter in town, if not the world. Within two short years, Graham went from being virtually penniless to amassing a significant fortune, setting him on a path to multimillionaire status.

In early 1968, an up-and-coming concert promoter in San Jose told the tale of how Bill Graham's goons showed up at his office with shotguns and made death threats. "No one promotes rock shows in the Bay Area without our permission… and you don't have permission!"

The suddenly-powerful music mogul quickly became known for throwing his weight around. In early 1968, an up-and-coming concert promoter in San Jose told the tale of how Bill Graham's goons showed up at his office with shotguns and made death threats. "No one promotes rock shows in the Bay Area without our permission… and you don't have permission!" The would-be competitor pulled their radio ads, canceled the show, and went into another line of work.

Those mob tactics might have been much more than an act. Bill Graham rubbed shoulders with New York mobsters upon returning from the Korean War (where he earned a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart in battle) in the early 1950s. He worked for years as a maître d' at upscale resorts in the Catskill Mountains of upstate New York. Graham often reflected on his tenure managing those establishments, hosting and promoting illicit poker games, which he said provided invaluable experience for his later role as a music promoter. Given that those resorts were under mob control and that he was intimately involved in illegal gambling, one could suggest he was closely associated with the Mafia.

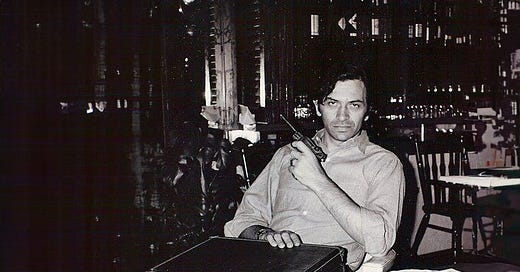

It was in 1922, at the tender age of 13, that Charles Sullivan ran away from home and made his way to California. He settled in San Francisco, where he attended night school to become a machinist. When the Union wouldn’t take him because he was black, he began chauffeuring for a wealthy Hillsborough socialite. By 1934, he took his savings and opened his first bar and restaurant. World War II brought Union acceptance, and he labored in San Francisco's shipyards. Post-war, Sullivan doubled down on entrepreneurship, beginning with liquor stores and eateries, a jukebox and pinball machine rental business, and then moving into hotels and nightclubs.

In 1954, he renovated an old dance hall and roller rink, renaming it the Fillmore Auditorium and transforming it into a cultural hub that came to be known as the "Harlem of The West." Sullivan's charm and business acumen saw him befriending legends like Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Duke Ellington and booking hot new acts like James Brown, Little Richard, and Ike & Tina Turner (to name just a few). He expanded his empire from San Diego to Vancouver and was soon named one of the richest black men in the West.

In the summer of 1964, race riots began breaking out in cities across America. The Fillmore district’s post-war job market dried up, leaving thousands unemployed. Crime rose rapidly, and Sullivan began carrying a gun in his briefcase. For the first time in his career, Charles Sullivan struggled to keep the Fillmore Auditorium fully booked. In December 1965, he was persuaded to sublease the venue to an ambitious would-be promoter named Bill Graham, who had been repeatedly denied a permit from the city.

Under Graham, the Fillmore Auditorium began booking psychedelic rock acts like Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother & the Holding Company, and the Grateful Dead. The new music brought a new audience—mostly white kids in their teens and twenties from the suburbs looking to experience the “San Francisco Sound.” The money poured in, and Graham begged endlessly to take over the lease and the music permit. But Sullivan never gave in.

Graham might have been booking the new acts, but it was Sullivan running the show and collecting a healthy cut of the money taken in at the door, and he continued promoting his own shows at the venue. In the Spring of 1966, Graham and Sullivan came to an agreement: Graham secured a contract for all open dates at The Fillmore that year, and a four-year lease option on the Auditorium if anything unforeseen happened to Sullivan.

On the last weekend of July 1966, Sullivan flew down to Los Angeles to oversee a James Brown concert. It was the last concert he would ever promote. He was dead a few hours after returning to San Francisco.

Before midnight on August 1, 1966, a woman in Oakland heard a man scream. She rushed out of her door and came face to face with a 6-foot-tall black man wearing an expensive suit. It was Charles Sullivan. He was nervously looking back over his shoulder and explained to the woman that he was leaving his girlfriend’s apartment (his mistress) and had seen a “kid” (perhaps a teenager?) walking toward him, and that it caused him to panic.

After going over and checking his car and ensuring the coast was clear, he said goodbye to the concerned neighbor and drove away.

Charles Sullivan was found shot dead at 1:45 am on August 2, 1966, near the corner of 5th and Bluxome Streets in San Francisco (a South of Market industrial area near the train station). He was lying between his rental car and a building, where a sidewalk would be if there was one, with a single bullet wound in his left chest and a .38 caliber pistol next to his right hand.

The San Francisco police have never officially concluded whether Sullivan's death was suicide or homicide. The city coroner ruled it a homicide, but SFPD Homicide Inspector Jack Cleary pushed his suicide theory in the media and refused to investigate further, even after being pressured by Mayor Dianne Feinstein to do so. Inspector Cleary would have us believe that Sullivan, at the top of his game and living his best life, drove to the deserted warehouse district after a successful show in Los Angeles to commit suicide, leaving no note for his wife and young children.

The fact that the very rich man, who was known to always carry a fat roll of cash, had only one dollar and six cents in his pocket didn’t bother the detectives in this case. Nor did the fact that $6,000 in cash from the James Brown show in Los Angeles was missing from an empty money bag which was found inside the open trunk of Sullivan’s rental car, which curiously had its lights on and motor running when police arrived at the scene–Sullivan must have been in one big hurry to get it over with.

“Listen here, young lady, don’t you ever tell Bill Graham that you’re Charles Sullivan’s niece. He might think you’re trying to find out who killed Charles,” he paused. “And we never had this conversation.”

The hardest thing to believe is that Charles Sullivan supposedly took his gun in his right hand and held it to the left side of his chest, shot himself through the heart and lungs, and then fell to the ground with the gun ending up next to his right hand. The awkward angle of the shot is one of the reasons that the coroner ruled out suicide.

The black-owned newspaper, Sun-Reporter, assigned Belva Davis to investigate the story, and she was told by a confidential source that powerful interests were behind Sullivan’s murder. Shortly thereafter, she was pulled off the story, and the newspaper stopped covering it. Sometime later, during a raid of Marion Sullivan’s speakeasy, a participating police officer made the family connection and told Marion he knew who killed his brother, but Marion was too afraid to follow up on the officer’s claims.

Harry R. Hall, who I went to school with at Cubberley High School in Palo Alto, was Sullivan’s nephew. He visited the Homicide Department at the SFPD to find out more about the case, but they brushed him off, telling him that the files would be hard to find down in the basement. He then went to the Coroner’s office and talked to a clerk. He discovered that there had been an Inquest hearing and that it was determined that the gun at the crime scene didn’t belong to Charles and that his gun was unaccounted for. Not only that, but no fingerprints of any kind were found in Charles’ rental car, and it wasn’t $6,000 that was missing–there was more than $40,000 missing from the money bag in the trunk.

Some years earlier, Harry’s sister wanted to approach Bill Graham about her t-shirt business and wound up talking to a booking agent at a show in 1985. She told the guy who she was, that she was Charles Sullivan’s niece, and that he was the one who opened the Fillmore Auditorium. The booking agent pulled her aside and said, “Listen here, young lady, don’t you ever tell Bill Graham that you’re Charles Sullivan’s niece. He might think you’re trying to find out who killed Charles,” he paused. “And we never had this conversation.”

Bill Graham himself never publicly went with the suicide story. He said it was murder and a robbery, "Charles Sullivan got himself killed. He had a bad habit of always carrying a roll of money with him. He was proud of his work and proud of the fact that he earned a good living and always carried a roll. He was jumped and stabbed to death. I went to his funeral in Colma, California. It was small, mostly family. Had that not happened, I think I would have done anything Charles wanted. Just out of gratitude."

Why Bill Graham said Charles Sullivan was stabbed to death is unclear. Maybe he misspoke, or maybe he was just confused.

On October 25, 1991, a helicopter carrying rock concert promoter Bill Graham, his girlfriend, and the pilot crashed into a transmission tower west of Vallejo, California. 300,000 volts of electricity killed everyone on board.

Be sure to check out Jon Kinyon’s personal blog: This Dude Thinks He’s a Writer.